10 Principles of Aphasia and Neuroplasticity

Published on Dec 14, 2019

The 10 Principles of Neuroplasticity are evidence-based ways to leverage neuroplasticity into treatment techniques for people with aphasia. Using these principles as a basis for therapy has been proven to help patients with physical, cognitive, behavioral and communicative impairments to maximize potential during therapy.

Furthermore, if these principles are leveraged in connection with an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) device they can lead to the most effective long-term use of the device.

When a speech-language pathologist (SLP) teaches an individual with aphasia to use an AAC device for communication, it’s important that he or she incorporate training techniques that allow the individual to be successful in their rehabilitation journey. Many times, SLPs turn on an AAC device and think, “How can I make this relevant for my client over the long term?” It’s a great question, and we believe that reviewing each principle of neuroplasticity and associating a complementary strategy that leads to greater device integration is the answer.

Here are the 10 principles and associated treatment exercises that can be conducted using a device during therapy sessions with an individual.

Principles & The Device Integration Strategies

- Use It or Lose It: Device users will benefit most from an AAC device if they use it daily. Failure to use it can lead to functional decline. SLPs can address this potential decline by programming phrases present in an individual’s daily conversations into the device, like “I would like a cup of coffee.”

- Use it and Improve It: Once the user has demonstrated the ability to select a single icon, they can improve upon that skill by combining icons or navigating through additional levels of the device.

- Specificity: The vocabulary present on a device impacts the user’s ability to communication effectively. For example, if a user has chronic back pain, SLPs should make sure the device has phrases supporting the pain scale or specific medication to address this need.

- Repetition Matters: When using a principle of neuroplasticity, it requires sufficient repetition. An SLP can achieve this building a routine around device usage.

- Intensity Matters: Plasticity requires sufficient training intensity. By using intense practice with a device user, SLPs can make sure the features designed to help the individual, like projecting icons, truly do help the user.

- Time Matters: Different forms of plasticity occur at different times after a stroke. By continuously revisiting the device training techniques at various stages of recovery, the user can maximize the neuroplasticity needed to effectively use the device.

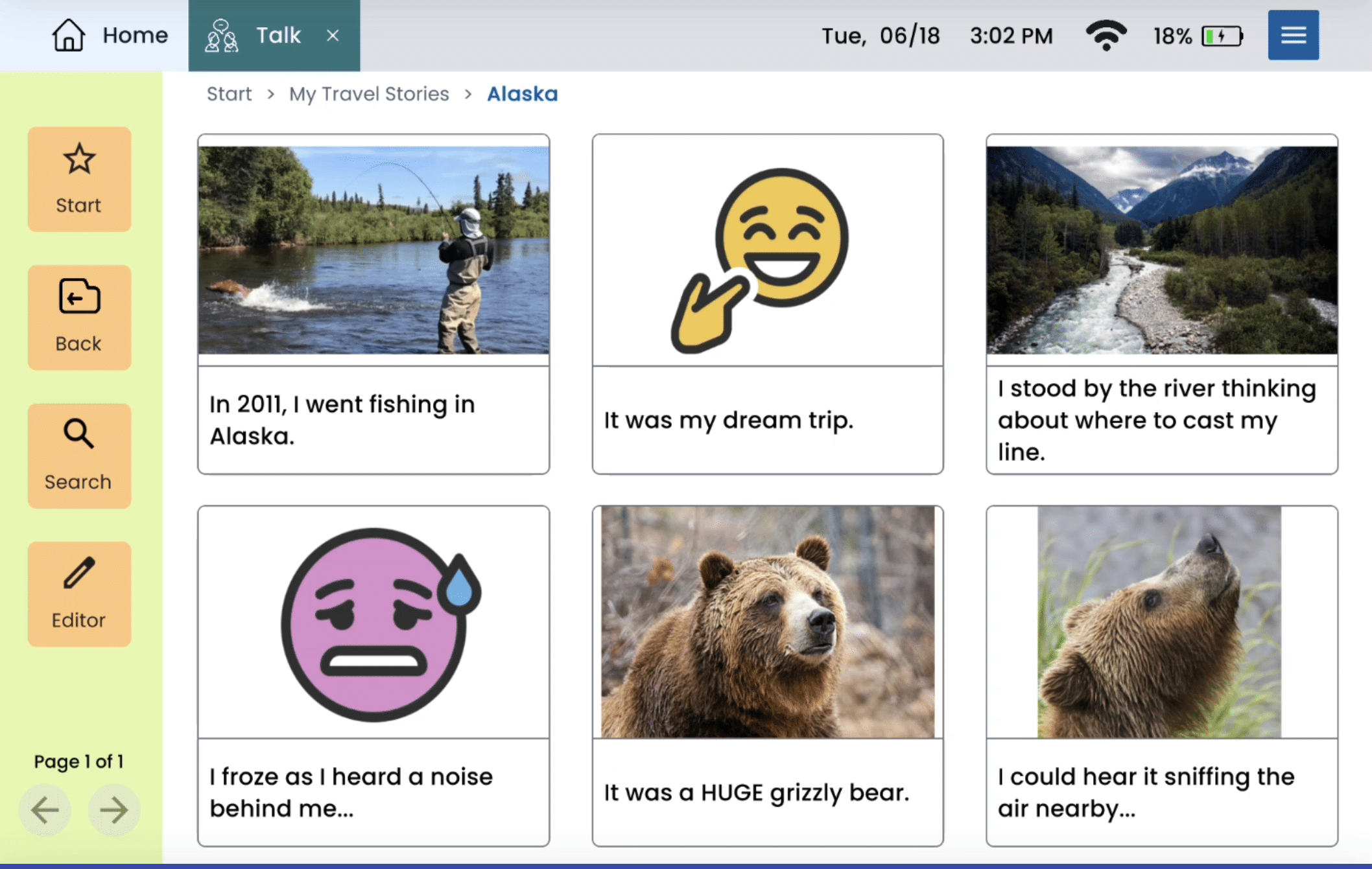

- Salience Matters: Whatever actions a user takes on the device, it must all tie back to something meaningful to the user. This could mean device messages around family, a favorite hobby or meal.

- Age Matters: Plasticity occurs more readily in younger brains; adult brains are still capable of plastic adaptation. An SLP may need to use more than one principle of neuroplasticity to encourage device usage with an older device user.

- Transference: Plasticity in response to one training experience can enhance acquisition of similar behaviors. An SLP can use the typing features to enhance an individual’s spelling skills.

- Interference: Plasticity in response to one experience can interfere with the acquisition of other behaviors. If a person with aphasia has developed compensatory strategies, the SLP might need to work harder to leverage neuroplasticity and retrain the brain for device usage.

SLPs might recognize many of these activities from daily therapy sessions. Armed with this knowledge and a deeper understanding of why clinicians use the techniques we do, SLPs will be able to advance their patients to the next level and introduce the next challenge.

About Contributor

Lingraphica helps people with speech and language impairments improve their communication, speech, and quality of life. Try a Lingraphica AAC device for free.